In Rebecca Devaney’s practice she combines artwork that is aesthetically pleasing, feminine and alluring with the investigation of underlying themes such as gender roles and their implications for women, social constructs of beauty and femininity, the interior and the exterior. Inspired and informed by 19th and 20th century Literature and Dress History that describe and illustrate the female perspective in regards to conforming to society’s expectations and the consequences of failing to do so. A narrative develops in each series using the redolent motif of dolls, that tells a story, intimates experiences, poses questions, and suggests alternatives.

Dolls

I have been your doll wife, just as at home I was Daddy’s doll child. And the children in turn have been my dolls. I thought it was fun when you came and played with me, just as they thought it was fun when I went to play with them. That’s been our marriage. -A Doll's House, Henrik Ibsen

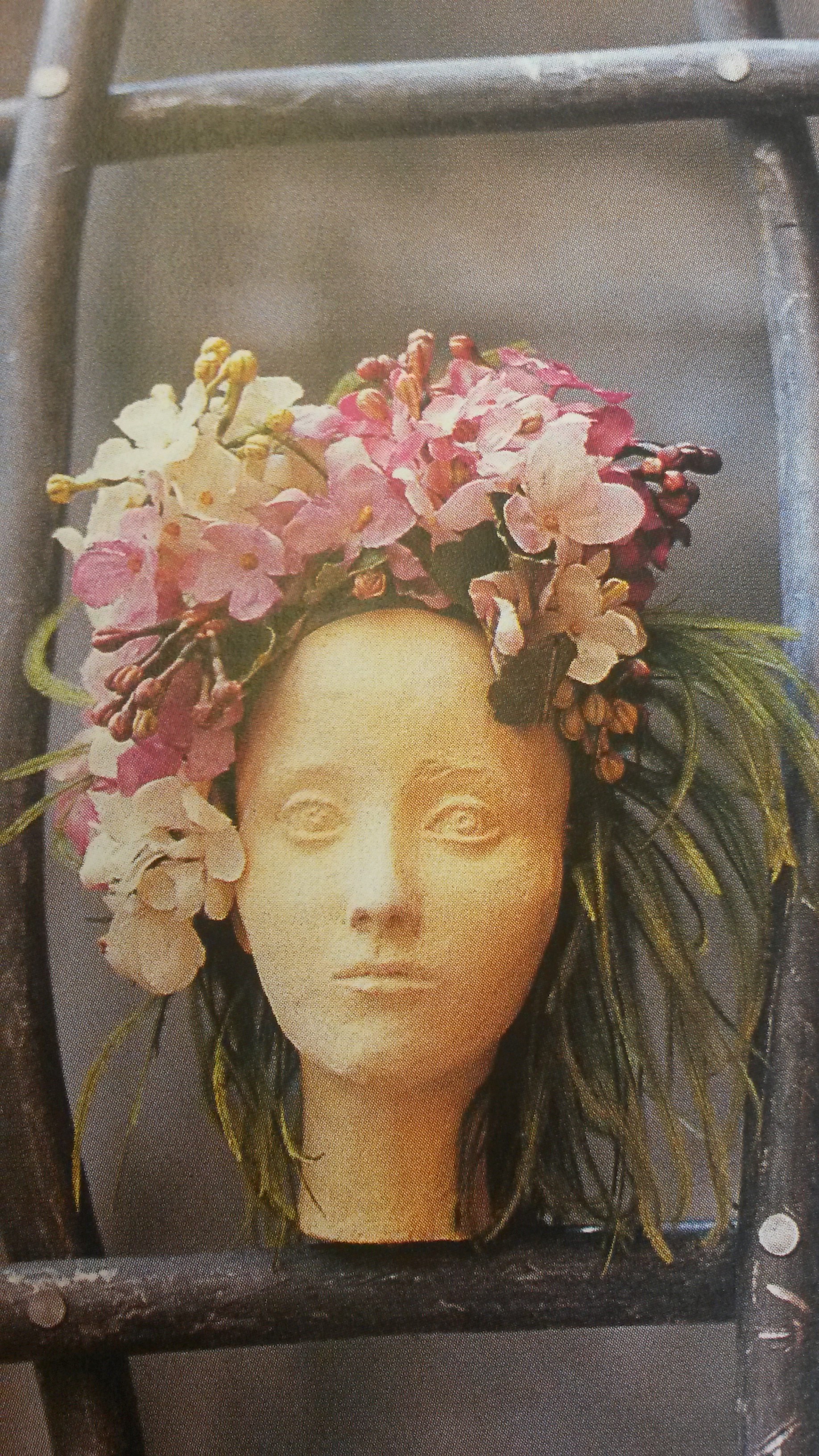

The poignancy of the above statement illustrates how dolls as an object of cultural reference may infer the inculcation of, and rigid adherence to established female gender roles and social expectations. As such they become contentious and imbued with negative connotations for may women. However, as a once cherished object of play, dolls may invoke sentiments of companionship, protectiveness and the innocence of childhood. They have brought hours of joy, amusement and pleasure to countless girls and will continue to do so. In exploring the tension that dolls may represent for women, it is also intended to celebrate them specifically for their femininity, they are dressed in lavish and ornate garments, they are informed by history, politics, economics and literature and they are engaging with emotional, intimate and shared experiences.

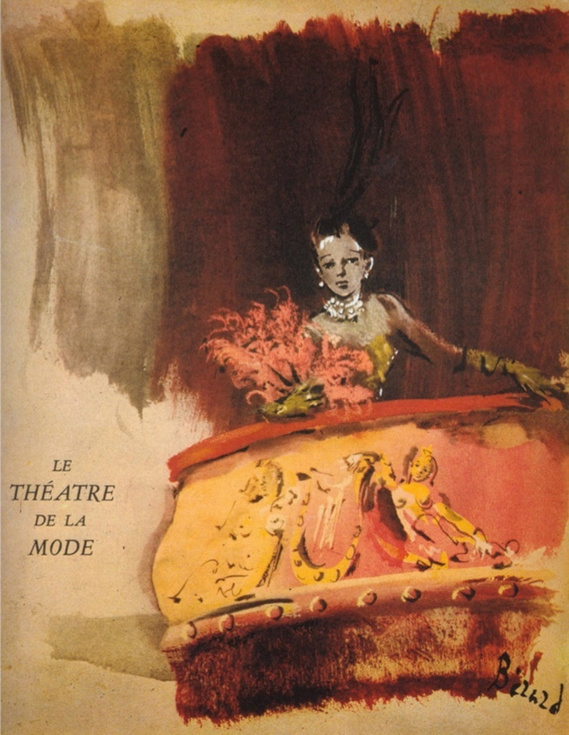

A spectacular moment in Fashion and Dress History was the Theatre de la Mode which was organised by the Chamber Syndical de la Couture and unveiled in March 1945, in the Pavillon Marson of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, France. Christian Bernard, the celebrated set designer for opera and theatre was the Artistic Director and he orchestrated a collaboration between the leading Haute Couture Houses in Paris such as Balenciaga, Pierre Balmain, Jacques Fath, Gres, Hermes, Jeanne Lanvin, Paquin, Schiaparelli, Worth, Nina Ricci, Jean Patou as well as artists, sculptors, set and lighting designers. They created an exhibition that showcased the very best of Parisian Haute Couture and their embroiderers, button-makers, milliners, shoemakers, glove makers, makers of handbags and accessories, jewellers and hairdressers on 237 exquisite miniature dolls set to the backdrop of 13 miniature stages. 100,000 visitors came to see the marvellous exhibition and it was an escape from the extreme trauma, hardship and austerity of World War Two to a world of breath-taking beauty and a celebration of Fashion, Art, Craft and Design.

Literature

Books such as Tess of the D’Urbevilles, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, My Brilliant Career, Pride and Prejudice, The Awakening, and The Bell Jar are enthralling in their descriptions of gender roles and social expectations for women in the 19th and 20th centuries. The lives of the female authors and the reception of their novels are often as captivating as the heroines and narratives themselves. Whilst Miss Havisham looms like a terrible spectre warning of the bitterness, loneliness and isolation of spinsterhood, Helen Graham, Sybylla Melvyn and Edna Pontillier offer a different perspective on women who choose to take a different path from the established norms..

Dress History

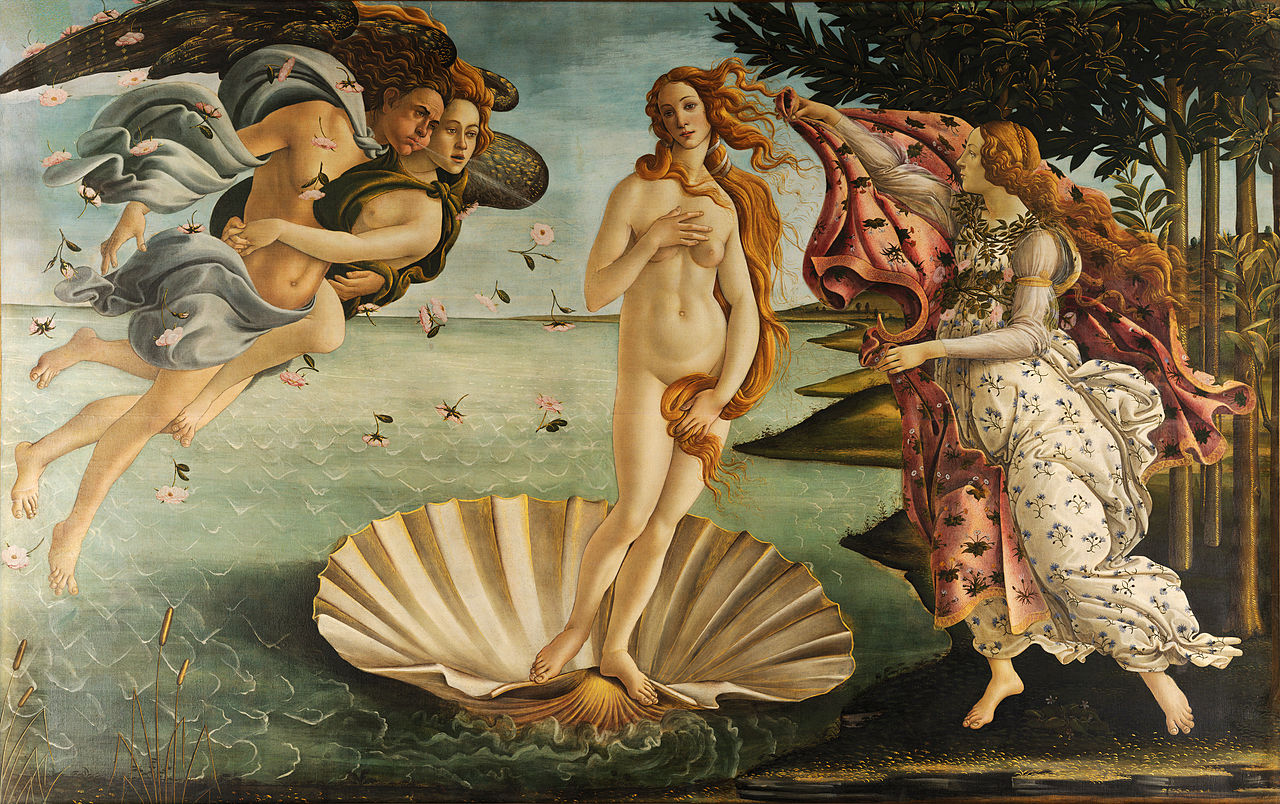

Looking at the paintings of Jean Honore Fragonard, Elisabeth Vigee Le Burn or Francois Boucher, the extravagance of Rococo fashions are depicted through sumptuous swathes of silk and satin fabrics, rich or pastel colours, delicate lace, fine feathers, trailing ribbons and twinkling jewels. They appear like delicious confections to marvel, covet and consume. Hours of pure enjoyment have been spent pouring over paintings such as these, wondering at the opulence of the beautiful dresses, their design, tailoring and construction.

Similarly, I love how the period costumes in theatre and film can transport you to a different era, not only because of the beautiful clothing but also due to the impressive historical accuracy and attention to detail displayed by the designers. The research and study of Dress History is fascinating in revealing how clothing may also convey a narrative about a person, whether that may be in a historical, social, cultural, political, economical or personal context. When viewed chronologically, European fashions during the Rococo, Neo-Classical, Victorian, Edwardian, and 20th century, may illustrate the ideals of beauty through changing silhouettes and the undergarments used to achieve them. The research of historical dress is an intrinsic element to my practise and whilst the influence may be visually apparent in the designs of the costumes, there is also reference to the role of dress in women’s experience of the world.

Beauty and Femininity

It is wonderful to be surrounded by beauty, to notice it, appreciate it, and create it because it enhances our world. As a social construct applied to women, it is transient and often seems arbitrary in it’s definition of the ideal. Yet throughout history women have gone to dangerous extremes to achieve what is considered beautiful and continue to do so today.

Looking up the definition of ‘femininity’ in the dictionary is still a surprising exercise and yet the qualities or appearances that are generally listed are pleasant in and of themselves. Of interest is the implications of femininity in the inculcation of gender roles for girls and women, particularly the experiences of those who struggle to conform to society’s expectations and the consequences or repercussions for those who do not.

The interior and the exterior

Dress is used to convey many aspects of a person’s identity and it has been artfully employed by women. Throughout history clothing was used to convey power, wealth, strength and influence by female leaders such as Boudicca, the Queen of the Iceni Celtic tribe, Cleopatra, the Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, the Roman Empress Theodora, Joan of Arc, Queen Elizabeth, Marie Antoinette and many more. This was deliberate, calculated to instil confidence and reverence. In the late 19th and early 20th century the Women’s Social and Political Union, founded following much frustration and discourse on their social and economic situation, donned a uniform in order to express their professionalism, dedication and determination to the derisive members of the media, politicians and society. Strong messages may be conveyed on a global platform through subtle or overt choice of silhouette, colour and jewellery as well as conforming to or deliberate eschewing of dress protocol at strategic occasions. In considering the lives of ancient, historical and contemporary female leaders from the exterior, it was paramount that the image they projected represented the power, wealth, morals, cultures, identities and values of their societies. In the necessity, choice or obligation to be a representative figure where is the space for self? What is held beneath the composed and constantly scrutinised surface, in privacy, in the interior, and is it ever explored, expressed or even acknowledged?

If the interior holds secrets, desires, frustrations, wishes, experiences, emotions, vulnerabilities, love, loss, anger, joy, pain, hurt, longing and truth then surely it is a sacred place as it would appear to contain what makes us human. And yet it is guarded vehemently or shunned disdainfully, caged in underwear, wrapped in beautiful clothing, protected, camouflaged and disguised.